Let’s take a snapshot of where we stand right now, remembering that the key ingredients for rain are both moisture and instability.

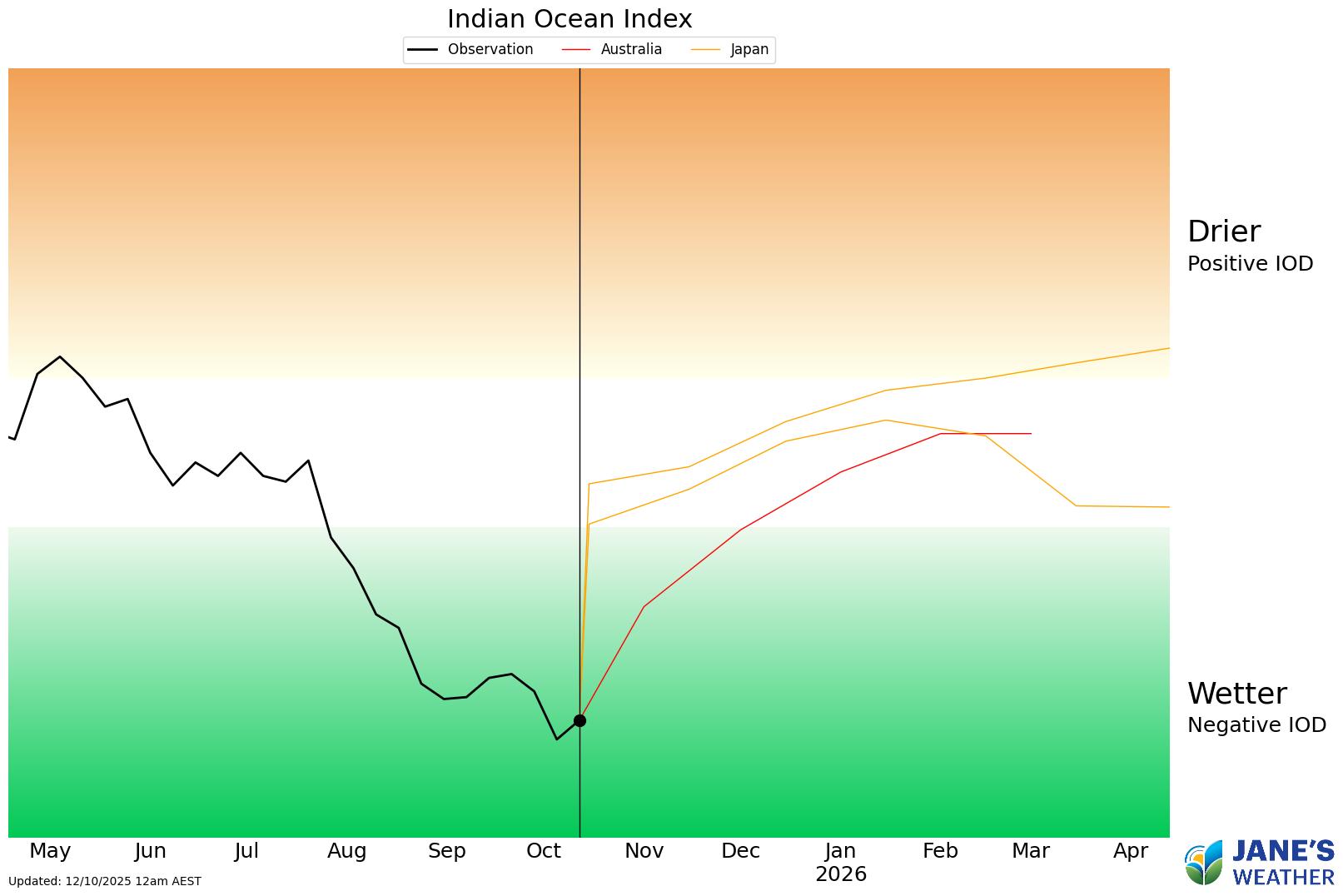

In the Indian Ocean we are currently in a Negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). Best known as the ‘La Nina’ of the Indian Ocean, in simplest terms you can think of this phase as actively pushing moisture towards Australia.

We crossed the threshold into Negative in late July, and it went seriously negative, what you would call ‘strong’. BoM declare these things after we’ve been in them for 8 weeks, which is why they only started mentioning it in late September.

This Negative IOD has been partly responsible for some spectacular rain. It shows up on the satellite as a juicy northwest cloudband, where you can see a huge band of cloud stretching from northwest WA down to southern Australia.

But that’s only one part of the rainfall equation - you need instability to turn that feed of moisture into rain.

In August, much of the drought affected areas of southeastern Australia (mainly SA to VIC to TAS) didn’t benefit much from the Negative IOD. The instability wasn’t ‘playing ball’ for these areas.

In September, much of SA to VIC continued to miss out, while Tasmania was absolutely walloped by front after front with above average rain.

In the first half of October Tasmania is still getting walloped, while much of the mainland southeast hasn’t seen much.

Around Australia we have large areas of warmer than average water, some significantly so. That releases more moisture into the atmosphere and gives us more moisture to play with.

In August and September it was a combination of a feed of moisture from the Indian Ocean, and from the Tasman Sea, both interacting with low pressure, that delivered significant rain to much of NSW, while southeast SA and much of VIC missed out.

This warmer than average water is here to stay as we go into spring and summer.

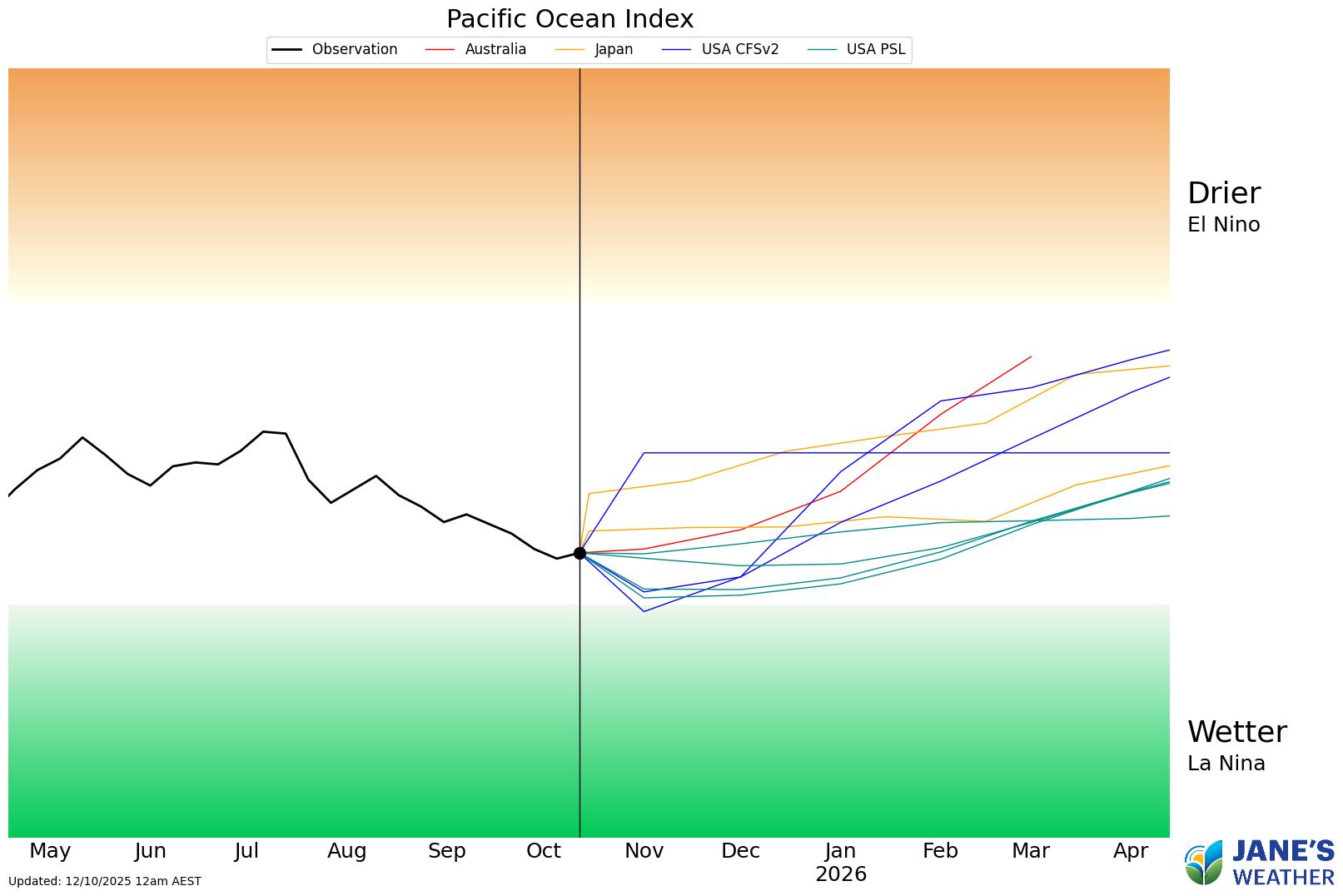

In the Pacific Ocean, the Americans have just declared La Nina (which is the fancy name for a Negative Pacific Ocean Index). BoM won’t declare this phase until we cross the Australian threshold which is a tougher one than what the USA uses.

Regardless, we will have plenty of moisture being fed in from the Pacific Ocean this summer.

The question is: where will that meet up with low pressure and deliver significant rain?

In much of Queensland and NSW there are troughs that set up each summer, ensuring an increased chance of wet weather. But in the southeast that is harder to predict, at the mercy of the weekly weather pattern.

.png)

.png)